This week, the 4C Health, Safety, Environmental Conference returns to Austin, Texas. Here are notes from a detailed class on pressure relief valves (PRVs) conducted by Emerson’s Dean Barnes, Warren Booth, Ricardo Garcia, Marcio Donnangelo, Marcelo Dultra, and Mo Fazl. Here is the abstract for this class:

Pressure Relief Valves are generally not well understood by environmental professionals. There is an assumption that rupture disks and pressure gauges serve to eliminate PRV emissions. The percentage of PRVs leaking to the atmosphere or to the process is much larger than generally believed.

Regulatory agencies are starting to understand the true impact of the pallet valves, cracked bellows and other PRV related sources. The true nature of these sources also becomes apparent with continuous monitoring whether it be LDSN or Hyperspectral Imaging.

This is a detailed class on the subtleties on the anatomy and nature of PRVs. If your organization can only send one person to the Conference – this is the high priority class.

Warren opened up by defining overpressure protection. The purpose is to protect personnel and property. They are the last line of defense in overpressure conditions in tanks, vessels, piping, and more. As such, they are essential safety devices that must meet regulatory codes.

The basic operation of a PRV is that it is a mechanical device that is self-operated. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) has codes for these safety devices. Warren described requirements for boilers & pressure vessels for maximum allowable working pressure (MAWP) limits, pressure relief rates, and how the fluids are disposed of. The American Petroleum Institute (API) has rules for hydrocarbon pressure relief. API provides standards and recommended practices but does not do compliance verification.

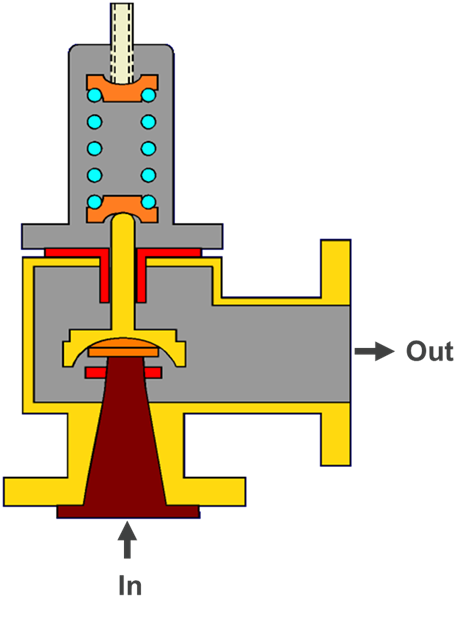

Warren next discussed a direct spring PRV. A spring supplies force to keep the valve closed, and when a pressure setpoint is exceeded, the pressure overcomes the force of the spring to open the valve and relieve the pressure. It’s a straightforward device. The valve reseats itself when the force of the spring exceeds the pressure. He described balanced direct spring designs to mitigate backpressure situations.

Dean came up to discuss pilot-operated PRVs. A pitot tube reads the system pressure and feeds it to the pilot valve. It feeds pressure back on the top of the valve piston, which is 30% larger in surface area than the bottom, to keep the force down. When the MAWP is reached, the pilot bleeds the pressure on top, the piston rises, and the PRV opens to relieve the pressure. The pilot can be a pop/snap action where the main valve fully opens at the set pressure. A modulating PRV has the main valve opening according to the relief demand. A modulating PRV acts like a backpressure regulator. The modulating PRV has become the most popular over time.

Pilot-operated valves are smaller and lighter than direct spring PRVs. The seat and reseat tightness are excellent. Some limitations are that they cost more in smaller sizes. At larger PRV sizes, pilot-operated can be better. The soft parts in the valve need to be matched to the process conditions.

Dean next spoke about safety selector valves. These devices enable safe and positive switching from an active PRV to a backup one. This Y-shaped selector has an active relief valve and a standby valve. A tandem arrangement is used when relief goes into a common header. The inlet and outlet safety selector switches are linked together to isolate the PRV that needs service and keep the other PRV in service to provide continuous overpressure protection.

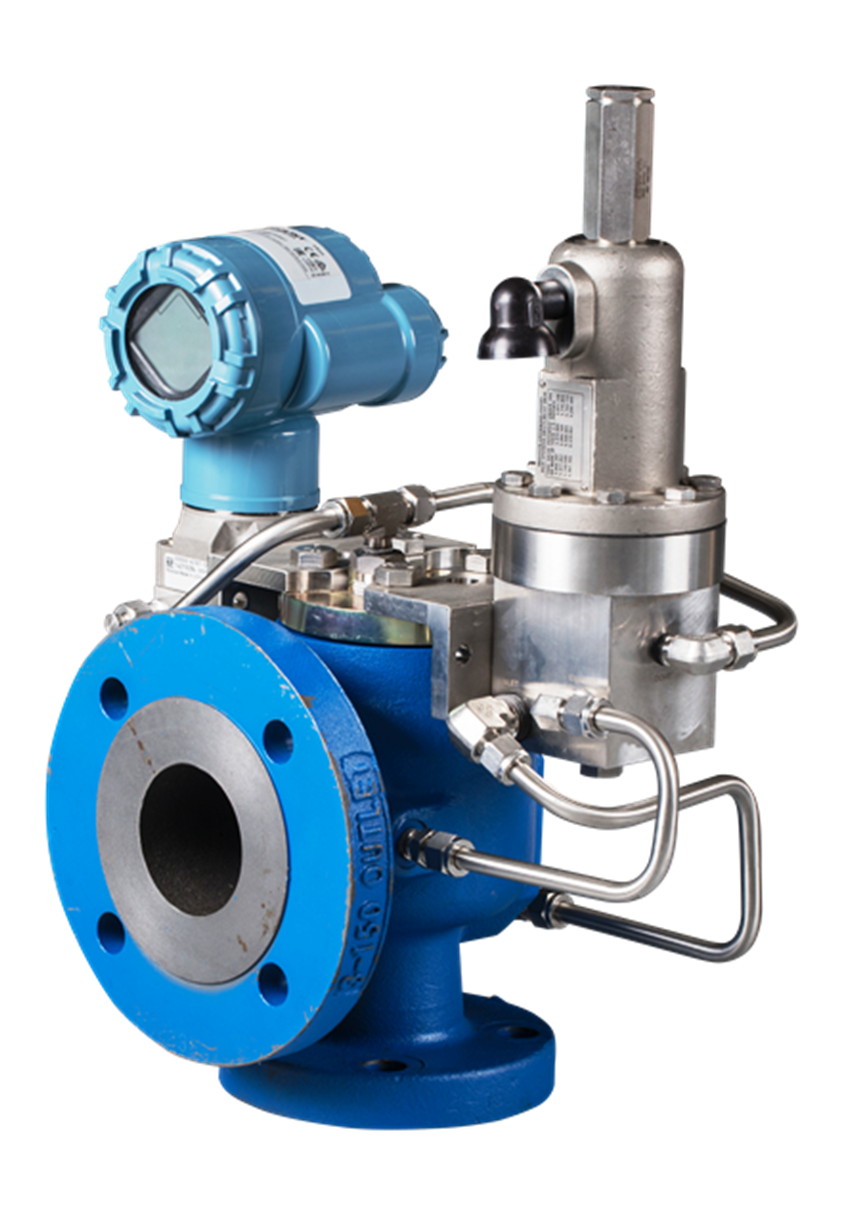

Marcio discussed pressure relief monitoring to detect conditions such as release events and leaks. Acoustic transmitters, in this case, the Rosemount 708 wireless acoustic transmitter, check for mechanical vibration in the pipe with peak sensitivity at 35-45KHz. Temperature is a secondary measurement to confirm which PRV is leaking. It’s looking for a direction change in temperature rather than the precise temperature.

The acoustic transmitter can identify if the PRV did not properly re-seat after a release event and identify a leak condition that requires service. The transmitter is put on the PRV outlet. The information from these and other wireless devices communicate via a WirelessHART mesh network to move the data to a gateway which feeds this information to built-for-purpose analytics apps to analyze the signals and determine release and maintenance-requiring events. The Plantweb Insight analytics application logs the start time, end time, and duration of the release event that can be used to satisfy the regulatory reporting requirements.

Ricardo came up to discuss another PRV monitoring technology. A solution for Crosby J-Series PRV using a valve position monitor to track the movement of the direct spring PRV piston. For a pilot-operated PRV, the area above the piston provides greater seating tightness, given the site configuration above being 30% larger than the bottom area. A differential pressure (DP) transmitter can tell when the two pressures are at equilibrium with the valve closed. When the system pressure increases and the dome pressure vents, the DP transmitter picks up the difference and identifies the release event.

PRVs may have bellows to deal with back pressure. When they fail, they can leak the process fluid into the environment through the bonnet vent. A pressure transmitter can monitor for a loss of pressure balance that the bellows address.

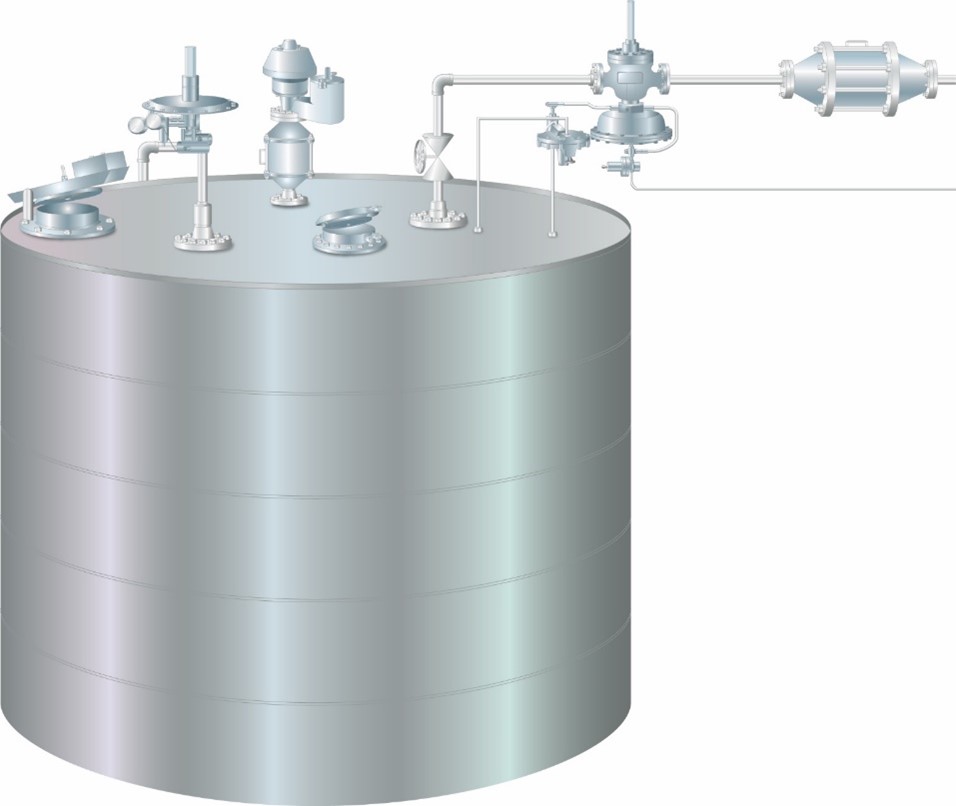

Mo finished up the class by discussing tank protection. These tanks often contain the valuable outputs of the production process that must be kept safe, and the personnel in the area kept safe. Mo discussed all the devices used for tank protection. He focused on fixed roof tanks which are the most common, but solutions exist for floating roof tanks.

Pressure control equipment includes vapor recovery, overpressure and vacuum relief valves, tank blanketing, emergency venting, and flame arrestors. For vacuum conditions, blanking gas compensates for product flowing out, oxygen inbreathing, and emergency inbreathing are next to avoid tank implosion. For overpressure conditions, vapor recovery followed by outbreathing prevents tank ruptures.

Pressure/Vacuum Relief Valves (PVRVs) come in many technologies. Weight-loaded PVRVs open as the over or under-pressure condition exceeds the weight. Full lift uses a huddling chamber design and goes fully open at 10% overpressure. Pilot-operated PVRVs are not affected by back pressure.

Mo next discussed emergency relief vent designs. The PVRVs should operate first to address abnormal pressure conditions and emergency relief vents set if the PVRVs don’t address the situation. Typically the PVRVs are set at 75% of the emergency relief vent settings.

Flame arrestors are used between the fuel source and the flame. They take away the heat to cause ignition. They act as heat sinks to remove the heat. Three types of flame arrestors are end of line, inline deflagration, and detonation arrestors.

Follow the links above for more information on these essential safety protection devices.